Research on Mediterranean Plant Communities in Sicilian Ecosystems

Date: May 2025 – ongoing

Activity overview: Field research on Sicilian plant communities through direct observation of natural habitats, study of phytosociology, and documentation of species associations, with the aim of applying these ecological principles to Mediterranean garden design.

1. How my interest in phytosociology and Mediterranean vegetation began

Sicily — extraordinarily rich in endemic species and Mediterranean habitats — felt like the right place to explore something that already felt deeply mine. While reading Flora of Sicily by the young Sicilian botanist Salvatore Cambria (who later generously shared his PhD research with me), I encountered the word phytosociology for the first time. I immediately connected it to plant-community-based design — the idea that certain plants naturally grow together in recurring associations, a concept widely studied in Anglo-Saxon ecological traditions.

I was driven by a simple but powerful curiosity: why do some plants choose each other in nature, while others never meet? I began studying plant associations at night, then searching for them in the field during the day, exploring nature reserves across the island.

It felt like stepping into a new world — complex, fragile, and constantly surprising.

2. The method I use to study plant communities

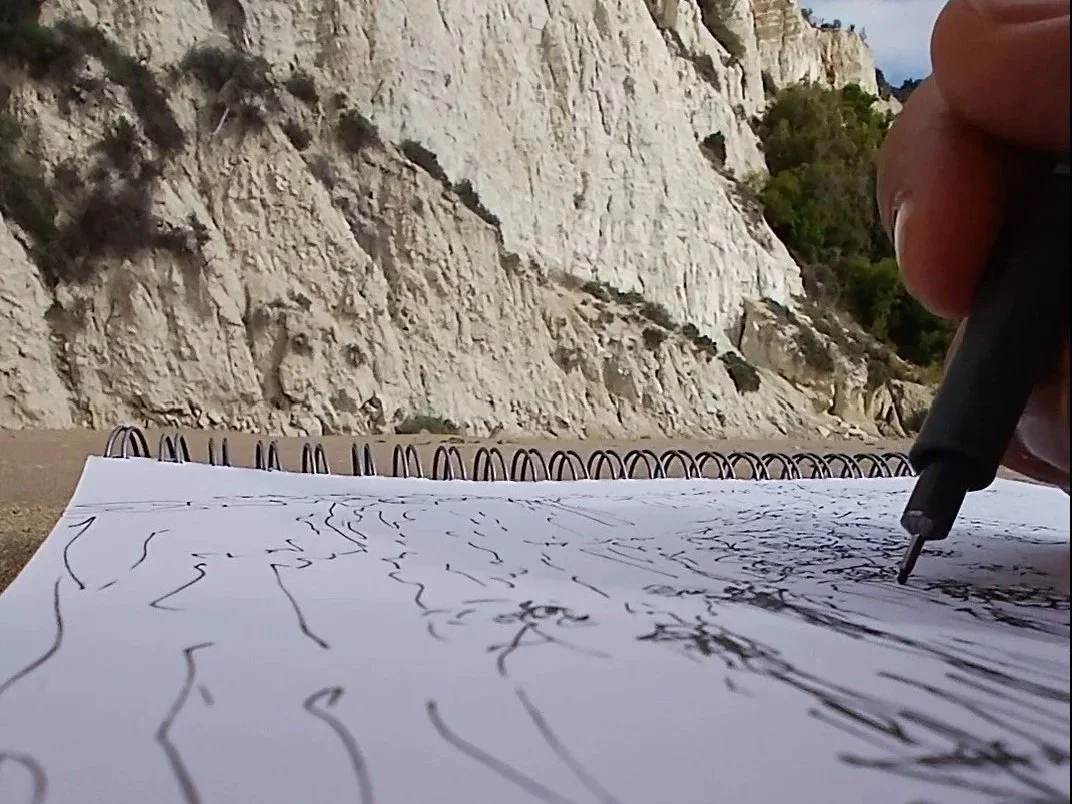

I have been experimenting with different ways of observing and understanding landscapes. At first, I was drawn mostly to visual qualities — light, plant forms, open spaces, and the small, natural paths winding between shrubs.

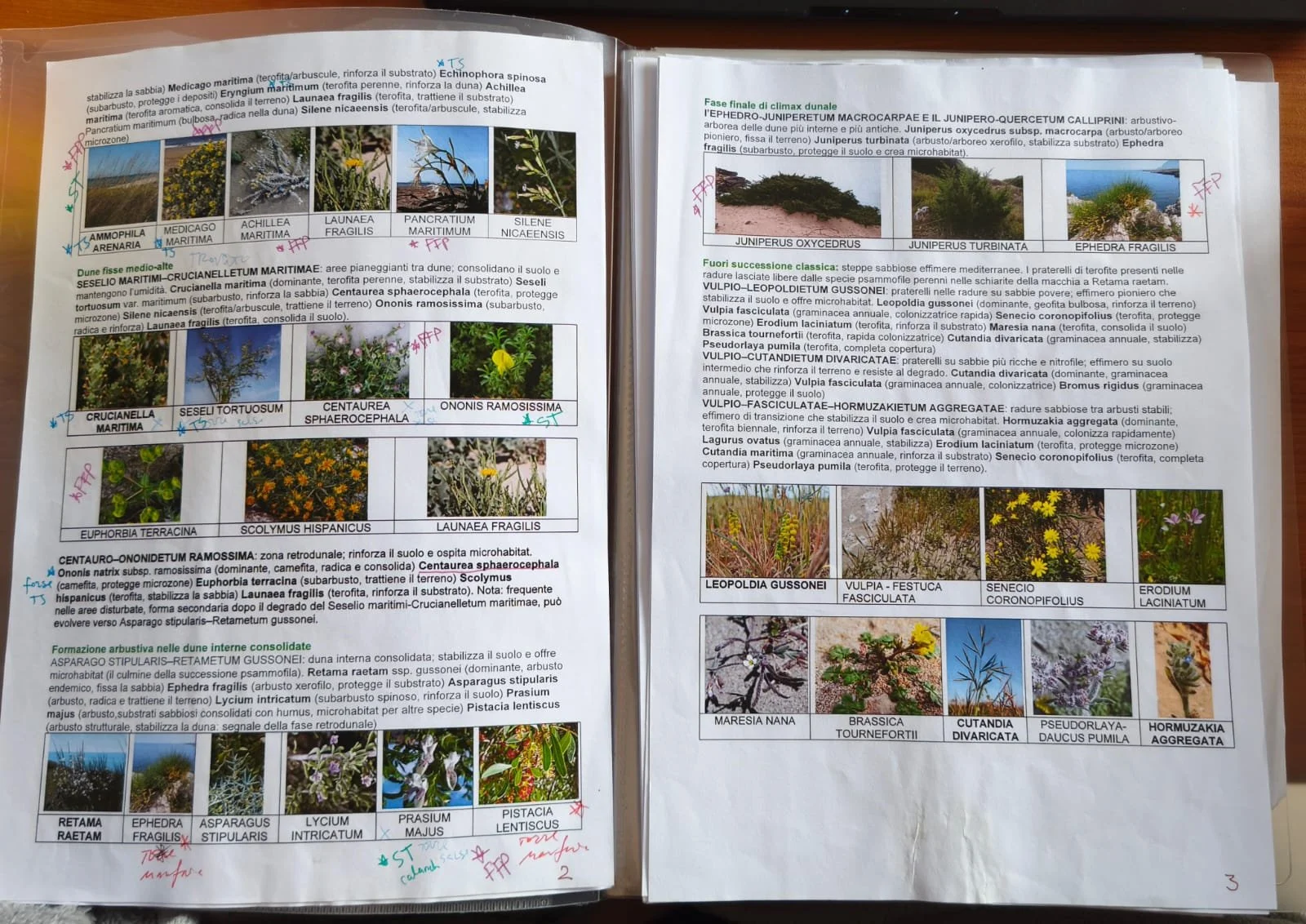

Then I felt the need to classify what I was seeing. I selected a specific Sicilian district, studied all the recorded plant communities there, and prepared field folders to carry with me. I took notes, photographs, and cross-referenced species, often supported by plant identification apps.

Whenever I identified a plant group described in the literature, it felt like a small celebration — even when it involved species I would never use in a garden. Over time, I learned to “read” landscapes more intuitively: I can now more quickly recognize the ecological stage of a site and sense the roles plants play within a system, while knowing nature never fully fits into neat categories.

What supports me in this work? My blue crossover car, safety boots in the trunk, printed plant-community sheets, a sketchbook, my phone — and above all, endless curiosity.

3. The main challenges in the field

Fieldwork comes with many challenges, often arriving when least expected.

Some places remain inaccessible due to mud or wild boars. Abandoned wooden ladders, leaning at near-vertical angles, sometimes become the only way back up a cliff. There are days when poor timing leaves me walking through a reserve in near darkness — no voices, no clear path. These are details that never appear in textbooks, yet they are as much a part of field research as the plants themselves.

Then there are the botanical frustrations: sometimes I find nearly all the species that define a plant community — except the dominant one. And without it, the association cannot be confirmed. It feels like finding a nearly complete puzzle with the central piece missing. So I begin again.

Soil is another constant challenge. It rarely matches the reassuring clarity of textbook categories. A slope can be both clayey and gravelly, holding unexpected minerals like a secret kept for millennia. Sometimes even a geologist cannot give me a clear answer.

4. The sensory experience of being in the field

Garrigue, grasslands, and dunes are pure light — open landscapes, warm wind, immense horizons.

Woodlands, in contrast, offer shade, protection, and a different rhythm.

Nature should not be idealized. One evening at dusk, I lost the trail in a reserve. My phone battery was dead, there was no one around, a small dead fox lay on the road, and a fallen tree blocked the path. I was scared. I started running until I met a young man walking a bulldog — the exit was fifty meters away.

This, too, is nature: welcoming and frightening, luminous and dark.

5. Plant communities that left a strong impression

One of the most fascinating associations to me is the one between Ephedra fragilis and Juniperus oxycedrus subsp. macrocarpa. Ephedra is slender and brittle — it snaps easily, which explains its name. The juniper, by contrast, has the dense texture of a conifer, a more irregular structure, and extremely slow growth: about ten centimeters per year. I observed them on the back dunes of the “Foce del Fiume Platani” nature reserve on Sicily’s western coast.

I am fascinated by how their different forms of fragility meet: Ephedra’s is physical, immediate to the touch; the juniper’s lies in its slowness, which is why juniper formations are protected even within reserves.

With equal elegance, Ephedra fragilis also appears in another Mediterranean community alongside Pistacia lentiscus, Phillyrea latifolia, and Teucrium fruticans in coastal cliff habitats. Here the other species are more robust, yet they have found a natural affinity, forming a balanced system.

6. The most important discoveries along the way

My first great discovery was dune ecosystems: extremely fragile environments where plants struggle daily against salt, wind, and storms, yet persist. They stabilize the sand and protect what would otherwise disappear.

Then came wetlands — marshes, ponds, small lakes. Slow ecosystems with an energy completely different from the sea or rivers. Resting places for migratory birds, temporary refuges that taught me how precious so-called “useless” landscapes really are.

Even a burned tree gave me a lesson. I first saw it as dead; instead, it was home, shelter, and nourishment for other forms of life. Even what appears finished still plays a role.

And then a major shift in perspective: discovering that garrigue and grasslands — landscapes I once idealized — are often degraded stages of Mediterranean scrub. Understanding ecological succession changed how I see everything. Each plant community prepares the ground for the next, moving toward woodland. In some contexts, Mediterranean scrub itself is the final stage of this evolutionary path.

7. How this is changing me as a landscape designer

This research has widened my perspective. I used to focus mainly on garrigue and scrub. Now I recognize transition zones and ecological dynamics. I often ask myself: what does a garden represent within this vegetational hierarchy?

I now look at ornamental plants with greater responsibility. A species I once loved, like Pennisetum setaceum, I now approach with caution — it is invasive and competes with local species such as Hyparrhenia hirta.

In this work, I inhabit two roles:

– the naturalist, who seeks to understand and replicate ecosystems

– the landscape designer, who intervenes creatively

I am still searching for the balance between the two.

8. My future vision

So far, I have explored around ten of Sicily’s seventy-eight nature reserves, and each visit has left a mark on me.

My future may not be tied to this land, even though I have deeply fallen in love with it this year. What I have found is my niche: designing Mediterranean gardens rooted in natural ecosystems.

I believe ecological design based on spontaneous flora is truly the future — green spaces that mirror natural conditions, where plants can grow without additional irrigation, fertilizers, or artificial inputs, just as they do in the wild.

My role is to read the land, listen to the landscape, choose the right plants, and support them through establishment. In this way, the garden becomes a living system — an autonomous organism that grows, breathes, and stands on its own roots.

And I would not be surprised if tomorrow I find myself in the Tuscan Maremma… or somewhere else entirely, continuing my endless exploration of nature.